Liskov Substitution Principle¶

Named after Barbara Liskov.

RULE: Objects should be replaceable with their sub-types without affecting the correctness of the program.

The “Is-A” way of thinking does not work well for every possible situation.

Solution 1: Break the hierarchy if it fails the substitution test.

Birds, Ducks and Ostriches¶

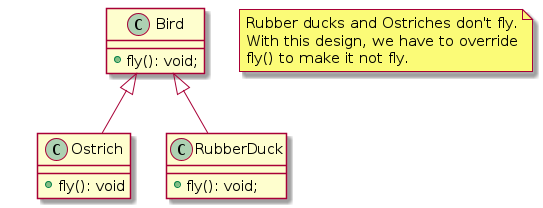

A rubber duck is a duck, but it doesn’t fly. An ostrich is a bird, but it doesn’t fly either. If a class Bird has a fly method, and RubberDuck and Ostrich classes inherit from (extends) Bird, what to do about the fly method in these two subclasses?

We cannot use a RubberDuck or an Ostrich in all the places we would use a “bird” because the fly method would have to NOT fly.

The Liskov Substitution Principle requires a test that is more strict than an Is-A test. We have to move away from the “Is-A” way of thinking.

If it looks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, but it needs batteries, you probably have the wrong abstraction. 😅

public class Bird {

public void fly() {

System.out.println("I'm flying!");

}

}

public class RubberDuck extends Bird {

@Override

public void fly() {

throw new RuntimeException("fly() method not implemented.");

}

}

The fly() method in RubberDuck changes the behavior of the program.

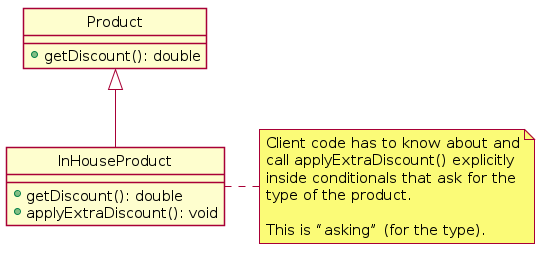

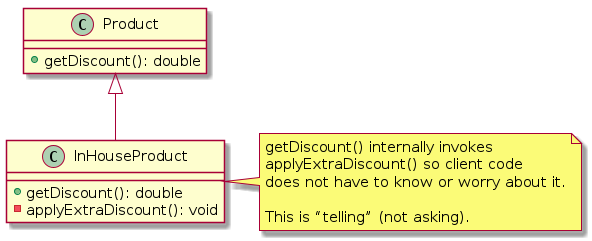

Products¶

Solution 1:

Cars¶

A racing car is a car, but it has a cockpit, while normal cars have cabins. You would have a getCabinWidth() for normal cars, but it would be wrong for racing cars, which should have a getCockpitWidth() instead.

A Racecar would have to override getCabinWidth() to do nothing, or throw a “not implemented” exception. It also would change the behavior of the program, and we would need conditionals in the client code to call the correct method depending on the type of the car.

The “solution” here is not to model the classes to exactly represent real world names of parts of the cars, but instead come up with generic names: getInteriorWidth (instead of getCabinWith() and getCockpitWidth()).

Instead of making Racecar inherit from Car, we instead create a new parent class called Vehicle which has this generic getInteriorWidth method instead. Each subclass then overrides getInteriorWidth() which just call getCabinWidth() and getCockpitWidth().

getCabinWidth(): Implementation with all the required logic for a cabin’s width;getCockpitWidth(): Implementation with all the required logic for a cockpit width;getInteriorWidth(): Parent class does nothing inside this method. Child classes override it and call their respectiveget … Width()methods.